Who was John Alexander McDonald?

Engineer, researcher and inventor

Engineer, researcher and inventor

John Alexander McDonald was a member of the Institution of Civil Engineers, London, the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, London and the American Society of Civil Engineers, New York. Born in London on 10 January 1856, he studied at King’s College, London, and after working for some time in England, he migrated to NSW in 1879 to superintend the erection of the iron bridges over the Parramatta River and Lane Cove, two of the largest bridges that time undertaken by the New South Wales Government. Upon the death of Bennett in 1889, McDonald was appointed Engineer for Bridges, a position he held until 1893.[30]

McDonald made a significant contribution to bridge design in NSW. His achievements include redesign in 1886 of the standard PWD truss to produce the McDonald truss; introduction of metal bottom chords in timber truss bridges for his 160 foot (48.5 m) span bridge over the Lachlan River at Cowra (thereby demonstrating the potential of the timber truss with all tension members in metal); design of all the lattice girder road bridges from 1884 to 1893, design of a series of sliding bridges at Lismore, Coopernook and Erina; and design of early bascule (drawbridge type) and lift bridges such as over the Darling River at Bourke.[31] He also designed two of the earliest steel beam bridges in NSW being the Unwin Bridge at Tempe and A’Becketts Creek Bridge at Parramatta. Two other engineers who joined the Roads and Bridges Branch at a similar time undoubtedly assisted, these being Percy Allan, who joined in 1878, and William Henry Warren, who worked in the Roads and Bridges Branch in 1881.[32]

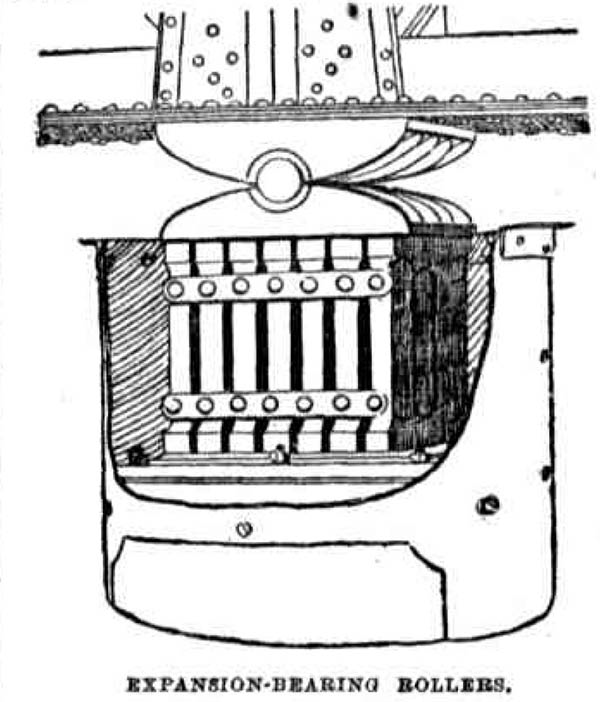

McDonald was also an inventor, and the patentee of “McDonald’s patent expansion rollers” for large bridges, used extensively in NSW, Queensland and America, and for which he received awards and medals at London, Chicago, Adelaide and Melbourne.[33]

(source: Australian Town and Country Journal, 10 March 1888, page 485)

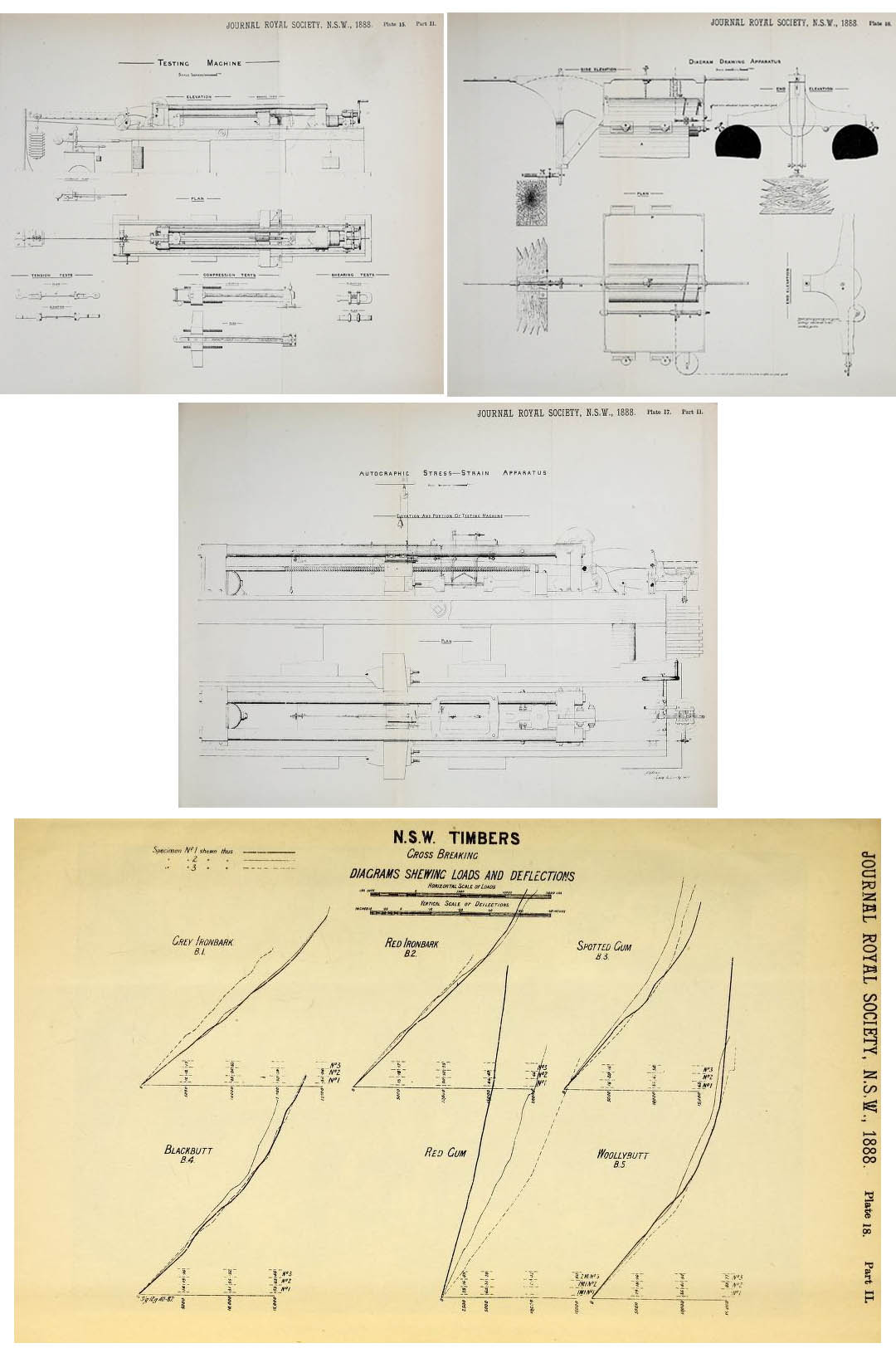

(source: Australian Town and Country Journal, 10 March 1888, page 485) McDonald was a collaborator in the University of Sydney timber testing and Warren gives him credit for the invention of an autographic strain recording device for the tests.[34]The diagrams show the device and some of the results produced. Little off-the-shelf equipment was available in those days so the device was made in the University of Sydney laboratory. McDonald commented in 1886 that Professor Warren’s testing had provided valuable and interesting data, “which every engineer in this colony has felt the need of and been unable to obtain with accuracy”.[35]McDonald was immediately able to use this data to design what has become known as the McDonald truss.

William Henry Warren was born in England in 1852 and migrated to Sydney in 1881 after working for the London Railways. In Sydney he worked in the Roads and Bridges Branch of the PWD while teaching applied mechanics at Sydney Technical College in the evenings. In 1882 he was appointed the first lecturer in engineering at the University of Sydney. An acknowledged leader of his profession, with a reputation extending beyond Australia, in 1919 Warren was the unanimous choice as first president of the new Institution of Engineers, Australia.[36]From his time working for the PWD, Warren noted the impressive range of hardwood timbers native to eastern Australia, as well as the fact that data on the properties of this resource was difficult to find in that no Australian testing facility of any reliability was available. At the University of Sydney, Warren obtained a Greenwood & Batley Testing Machine in 1886.[37]On the 1st December 1886, he was able to report to the Royal Society of New South Wales the results of testing of ironbark timber.[38]

Later years

After 14 years of service McDonald was retrenched.[40]Some of the other Departmental Heads did not appreciate the sardonic trait in his character, bringing them into conflict.[41]One of the engineers that later worked with McDonald in South Africa, however, testified to the valuable assistance he had received from him, and to his high professional qualifications as well as to the judgment, tact, and courtesy which had always been conspicuous features of his administration.[42]

McDonald then spent six months in the United States before returning to take up a position as Assistant Engineer to the Public Works Department in Western Australia and then Resident Engineer for Freemantle Harbour Works. In 1898 McDonald moved to South Africa, where he engaged in mining, designing electric light stations and various other activities until 1908, when he returned to Australia and tried his hand at farming. In 1912 McDonald moved to Gisborne, New Zealand Zealand in 1912 as Engineer and Secretary to the Gisborne Harbour Board. As he had done at Fremantle, he developed the shipping facilities of the port through the use of dredges to widen and deepen the entrance channel. As a well-qualified professional man who “did not have to come to Gisborne to make a reputation” McDonald had felt he could be blunt with the Board. He was a chronic sufferer of insomnia and apparently his ill-health made him fractious and difficult to work with. Marion, his wife of many years passed away on 1 February 1917 and was described as his beloved friend and companion. Following this he was reported to have had numerous squabbles with the Board and fell out with them and was dismissed in September 1917.

He was too brilliant an engineer in a town of 10,000 for his talents to go to waste. He was thus engaged over the next 6 years as Resident Engineer and later Consulting Engineer to the Gisborne Borough Council. He designed the concrete bridges on the two main crossings in the city at Peel Street and Gladstone Road which are both extant. These were considered advanced technologically for the region when completed in 1923. He married Blanche De Warrenne Commins (herself a widow) in 1919. Now aged 67 his health began to deteriorate and sadly he emulated his former colleague C.Y. O’Connor and ended his life with a bullet to the head on 4 June 1930 aged 74 at his home in Gisborne. John A McDonald is buried in Taruheru Cemetery (Section 1, plot 51) Gisborne, New Zealand beside his first wife.[43]

References

[30]"The Harbor Engineer," Poverty Bay Herald (New Zealand), Thursday 11 December 1913, p 7.

[31] Lynn Heather Mackay, Iron Bridges in N.S.W, An Essay, University of Sydney, 1972, pp 31-35.

[32] Arthur Corbett, 'Warren, William Henry (1852–1926)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/warren-william-henry-4804/text8007, published first in hardcopy 1976, accessed online 4 September 2017.

[33] “The Harbor Engineer”, Poverty Bay Herald (New Zealand), Thursday 11 December 1913, p 7.

[34] Ian Bowie, “Australia’s First Materials Testing Machine”, ASHET News, Vol 3, No 4 Oct 2010, pp 4-6.

[35] William Henry Warren, The Strength and Elasticity of Ironbark Timber as applied to Works of Construction, read before the Royal Society of NSW 1-12-1886, p 275.

[36] Arthur Corbett, 'Warren, William Henry (1852–1926)', Australian Dictionary of Biography.

[37] Ian Bowie, “Australia’s First Materials Testing Machine”, ASHET News,Australian Society for History of Engineering and Technology Newsletter, Vol 3, No 4 Oct 2010, pp 4-6.

[38] William Henry Warren, The Strength and Elasticity of Ironbark Timber as applied to Works of Construction, read before the Royal Society of NSW 1-12-1886.

[39] Professor Warren, Description of the Autographic Stress-Strain Apparatus, Read before the Royal Society of N.S.W., August 1, 1888, Journal & Proceedings Royal Society NSW 1888, pp 253-256 and plates 15-18.

[40] Annual Report of the Department of Public Works to the Legislative Assembly 1894, p 123.

[41] Henry Harvey Dare, Tales of a Grandfather 1867-1941, unpublished autobiography, p 28; Lynn Heather Mackay, Timber Truss Bridges in New South Wales, Thesis, Bachelor of Architecture, 1972, p 74.

[42] “Harbor Affairs”, Poverty Bay Herald (New Zealand), Tuesday 20 February 1912, p 4.

[43] “Shot Through the Head: John A. McDonald”, Poverty Bay Herald (New Zealand), Wednesday 4 June 1930, p 7.