The European through truss and Queen Post deck truss

Approximately seven European through type timber truss rail bridges were built between 1875 and 1894, with only one remaining in 2021. Approximately seven Queen Post deck type timber truss rail bridges were built between 1860 and 1889, with six remaining in 2021.

These timber truss rail bridge designs were copied from railway structures in use in England, designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806-1859) and comparatively little innovation or development occurred in NSW, in contrast to the situation for timber truss road bridges. Although none of Brunel’s timber truss rail bridges remain in the UK, a number remain in New South Wales. Unfortunately, none have carried trains since at least the 1980s.

Bridge engineering for the railways of NSW from 1850 to 1915 had two eras of dominant technologies, British until 1890 and American after 1890. The British era covered the long term in office of the Yorkshire-trained ‘father of NSW railways’ John Whitton. Under Whitton’s authority, the European and Queen Post trusses were built. Whitton was ill-disposed to American bridges and to timber bridges, which might explain why timber truss rail bridges make up less than 10% of the total number of NSW timber truss bridges constructed.

Source: Brunel’s Cornish Viaducts, John Binding, pages 48-49, from the L G Booth Collection.

Source: Brunel’s Cornish Viaducts, John Binding, pages 48-49, from the L G Booth Collection.

Source: Brunel’s Cornish Viaducts, John Binding, pages 58-59, from the L G Booth Collection.

Source: Brunel’s Cornish Viaducts, John Binding, pages 58-59, from the L G Booth Collection.  Source: Brunel’s Cornish Viaducts, John Binding, page 25, from the B Ward Collection.

Source: Brunel’s Cornish Viaducts, John Binding, page 25, from the B Ward Collection. The Nottar, Weston Mill and Forder Viaducts are all examples of Brunel’s standard short span through truss design in timber, which is very similar to Whitton’s European through truss. The viaduct over the River Neath and the Stonehouse Viaduct are examples of Brunel’s standard short span deck truss design in timber, which is almost identical to Whitton’s Queen Post deck trusses.

Source: Brunel’s Timber Bridges and Viaducts, Brian Lewis, page 74, from M Jolly Collection.

Source: Brunel’s Timber Bridges and Viaducts, Brian Lewis, page 74, from M Jolly Collection.  Source: National Museum Wales, digital record #IBASE 435.

Source: National Museum Wales, digital record #IBASE 435.  Source: Brunel’s Timber Bridges and Viaducts, Brian Lewis, page 47, from the Alastair Warrington Collection.

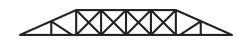

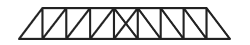

Source: Brunel’s Timber Bridges and Viaducts, Brian Lewis, page 47, from the Alastair Warrington Collection. The main difference between the European through truss and the Queen Post deck truss is whether the trains travel between the trusses (the through truss) or above the trusses (the deck truss). The deck truss was preferred if floods were not anticipated to reach the truss timbers, but where additional clear height was required, the through trusses were constructed.

Bill Phippen gives an explanation for some of the other differences between the two designs:

“In all the queen-post truss bridges built on the New South Wales Railways, those above the track level – through trusses – had diagonal members in the centre panel between the queen-posts and a substantial vertical tension member – a large bolt – in the centre of the span… The queen-post trusses below the track level – deck trusses or transom-topped trusses – had no diagonal and no tension bolt… The practical reason for this difference may be that with the deck truss the live load bears directly on the very large top chord which with a section of up to 20-inches by 12-inches can readily span between the queen posts. The track not carried by the top chord is supported from the pier top by vertical and inclined struts. In the case of the through truss, the live load is carried by the bottom chord and this is of a smaller section which does need support between the queen-posts, hence the bolt and the diagonals.”[19]

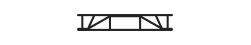

The design of timber truss rail bridges took a separate path to the design of timber truss road bridges, and there appears to be very little overlap. This may be, in part, due to the different design loads. While road bridges in the late 1800s were designed for a 16-tonne traction engine, rail bridges had to be designed to carry at least a 100-tonne steam locomotive. For this reason, rail trusses have much shorter spans that road trusses.

Timber truss road bridges were constructed with spans varying from about 50’ (15 m) to a maximum of 165’ (50 m), with most spans being around 30 m in length. Timber truss rail bridges, however, have much smaller span lengths, varying from 32’ (10 m) to a maximum of 62’ (19 m), with most spans being around 12 m in length (see diagram below).

Lewis describes some of Brunel’s innovations which were taken up by both the road and the rail bridge designers in NSW. Timber bridges and viaducts were widely used on Britain’s railways well into the 1860s, but Brunel made greater and more consistent use of this medium and certainly developed a number of designs with a mind to graceful appearance as well as economy and ease of maintenance. Although it is not possible to say with certainty that Brunel was the first engineer to introduce cast iron shoes in the construction of timber bridges and viaducts, he undoubtedly made the most extensive and consistent use of them. Other engineers would often be content with a wrought iron strap connecting the surfaces of a joint.[20]

As noted above, none of Brunel’s timber truss bridges survive in the UK, but the bridges in NSW demonstrate some of the unique qualities of NSW hardwoods that were plentiful in NSW at that time and were known to be among the strongest and most durable in the world.

References

[19]Bill Phippen, 2020, The Timber Truss Railway Bridges of New South Wales, ISBN: 978-0-6488842-0-0, p 14.

[20]Brian Lewis, Brunel’s Timber Bridges and Viaducts, Ian Allan Publishing, England 2007, pp 7 & 24.